Fourth Year Medicine (Undergraduate)

University of New South Wales

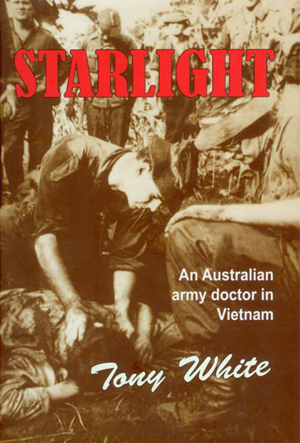

White T. Starlight: An Australian Army doctor in Vietnam. Brisbane: CopyRight Publishing; 2011.

RRP: $33.00

Not many of us dream of serving as a medical doctor in the frontlines of war. War is after all the antithesis of everything the medical profession stands for. [1] In Starlight, Dr Tony White AM vividly recounts his tour of duty in South Vietnam between 1966 and 1967 through correspondence exchanged with his family. STARLIGHT was the radio call sign for the medical officer and it bore the essence of what was expected of young White as a Regimental Medical Officer (RMO) in the 5th Battalion of the Royal Australian Regiment (5 RAR).

White was born in Perth, grew up in Kenya and read medicine in Clare College, Cambridge University. After completing the first half of the six-year degree, he moved back with his family to Sydney where the pivotal decision to join military service was made. White accepted a scholarship from the Australian government to continue at the University of Sydney in exchange for four years of service in the Australian Defence Force after a year of residency.

In May 1966, White’s wartime duties commenced with 5 RAR in Vung Tau, southeast of Saigon, dubbed “Sufferer’s Paradise”. After a brief settling-in, the battalion moved to Nui Dat, their operational base for the year. The initial excitement of the 25-year-old’s first visit to Asia quickly faded as the realities of war – the mud, the sweat and the blood – set in. Footnotes and explanation of military jargon and organisation were immensely helpful in acquainting the reader to the battalion’s environment. As an RMO, White worked round-the-clock performing General Practice duties such as sick parades and preventive medicine, emergency duties attending to acute trauma, and public health duties monitoring for disease outbreaks and maintaining hygiene. The stark difference from being a civilian doctor is candidly described, “You live, eat, dig, and [defecate] with your patients and, like them, get every bit as uncomfortable and frightened. There is no retreat or privacy.”

From the early “friendly fires” and booby traps to the horror of landmines, White’s affecting letters offer a very raw view of war’s savagery. It was a war fought against guerrillas, much like the present war in Afghanistan, where the enemy is unknown and threat may erupt into danger at any time. During the numerous operations 5 RAR conducted, White attended to and comforted many wounded. With every digger killed in action, a palpable sense of loss accompanies the narration. White clearly laments the “senseless killing of war” as he explained, “You spend all that time – 20 years or so – making a man, preserving his health, educating and training him, to have him shot to death.” White himself had close brushes with death. He was pinned down by sniper fire on one occasion and even found himself in the middle of a minefield in the worst of tragedies encountered. The chapter “Going troppo” ruminates on the enduring psychological effects of these events as the year unfolded.

The insanity of war is balanced by many heartening acts. First and foremost is the remarkable resilience of the diggers whose tireless disposition to work inspired White profoundly. White also voluntarily set up regular clinics in surrounding villages to provide care for civilians despite the threat of enemy contact. In an encouraging twist, both friendly and enemy (Viet Cong) casualties were rendered the same standards of care. Even more ironic was the congenial interactions between the two factions within the confines of the hospital. Perhaps the most moving of all was White’s heartfelt words of appreciation to his family who supported his spirits through sending letters and homemade goodies like fruitcakes, biscuits and smoked oysters.

So why should you read this book? Textbooks do not teach us empathy. White shares in these 184 pages experiences that we all hope never to encounter ourselves. Yet countless veterans, refugees, abuse victims, etcetera have faced such terror and our understanding of their narratives is essential in providing care and comfort. In the final chapters of this book White gives a rare physician perspective on post-traumatic stress disorder and how he reconciled with the profound impact of war to achieve success in the field of dermatology. These invaluable lessons shine through this book.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

References

[1] DeMaria AN. The physician and war. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2003;41(5):889-90.

Download PDF

Download PDF Read online

Read online You can subscribe by e-mail to receive each issue when it's published.

You can subscribe by e-mail to receive each issue when it's published.

Download the issue

Download the issue Print this extract

Print this extract Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook